How the rise of Clint Eastwood gave John Wayne anxiety: “What do people see in these films?” - Far Out Magazine

The rise of Clint Eastwood gave John Wayne anxiety because he felt threatened by his stardom and he believed his revisionist westerns were too nihilistic.

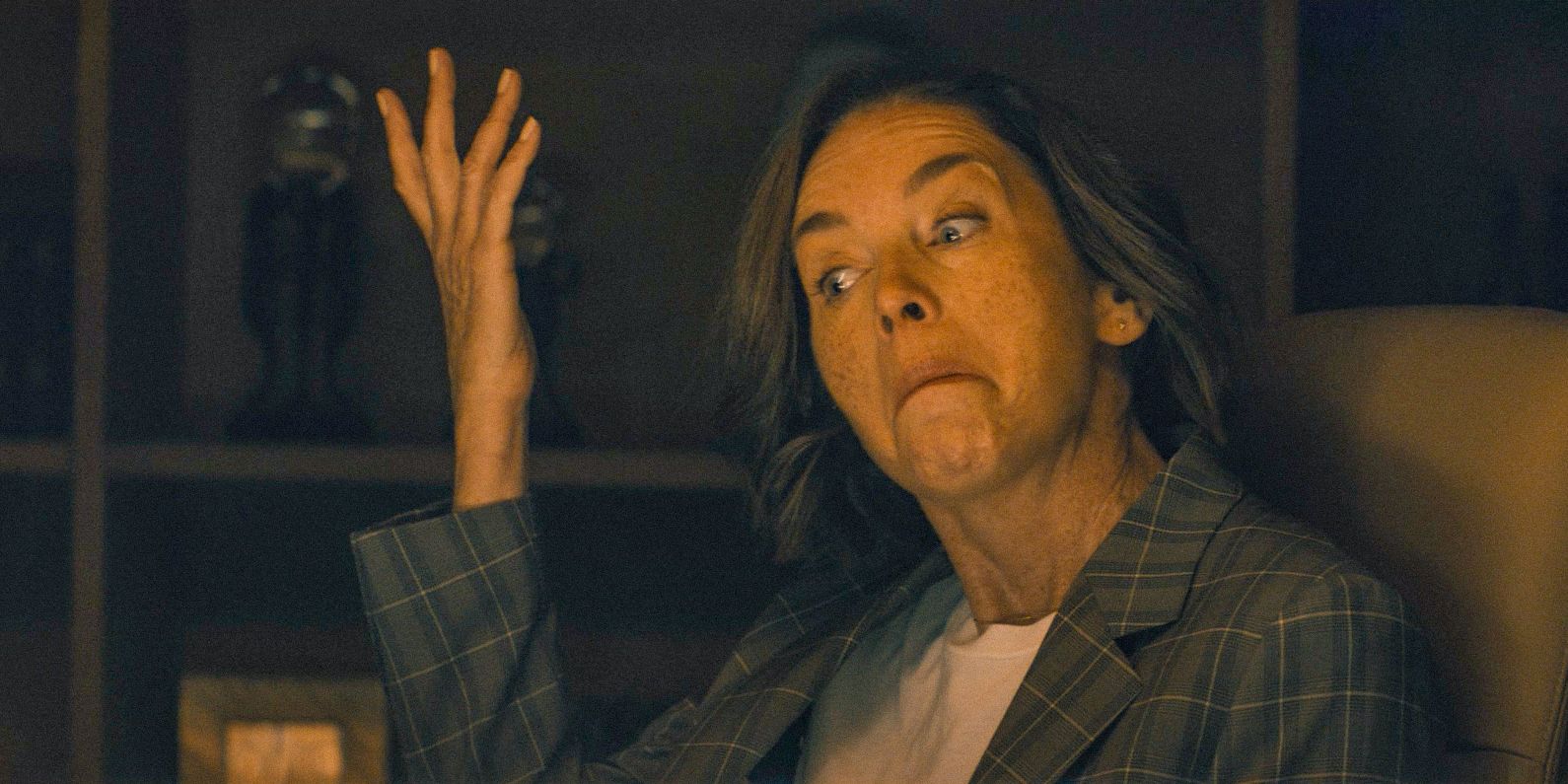

(Credits: Far Out / MUBI / Universal Pictures)

Film » Cutting Room Floor

Fri 7 February 2025 17:45, UK

When Clint Eastwood emerged from the strictures of TV’s Rawhide and took a fateful sojourn to Italy to make some genre-defining westerns with Sergio Leone, one man nervously side-eyed what was happening. You see, at that time, John Wayne was a few years removed from pictures like The Alamo and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and he was wary of a future barrelling toward him that he didn’t like the look of. Wayne wasn’t a fan of what Eastwood was doing with the genre that had made him an icon, but he had to acknowledge that audiences felt differently – which gave him colossal anxiety.

By the time Eastwood exploded onto the scene in 1967 with A Fistful of Dollars, A Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Wayne was already well into his fourth decade as a movie star. These Spaghetti westerns, as they came to be known, had been released in Italy in ’64, ’65, and ’66, so by the time all three were unleashed on the American moviegoing audience in ’67, a significant buzz had already built.

When audiences sat down to watch Eastwood and Leone’s efforts, though, they saw that the western genre had been turned on its head. These weren’t the simple, good vs evil stories that had defined so many of Wayne’s westerns. Instead, they were ugly, violent, morally compromised tales in which there were few good guys and everyone – the lawmen, the outlaws, and even the townspeople – were largely out for themselves. Over the years, this western brand was dubbed “revisionist,” as it attempted to revise the false impression that had been given of the Old West by Hollywood – and Wayne wasn’t a fan.

“I was getting anxious because there was this young guy called Clint Eastwood making westerns in Italy and having tremendous success with them,” Wayne admitted in an interview in the late ’60s. “All of a sudden, the studios all wanted Eastwood to come and make westerns for them, but they were not the kind of westerns I’d been making. They were tough and bleak.” Indeed, Wayne was so shocked and put off by what Eastwood depicted on screen that he exclaimed, “I don’t get it. What do people see in these films?”

Amazingly, Wayne was so disgusted by 1973’s High Plains Drifter – Eastwood’s second directorial effort – that he wrote a letter detailing what offended him about it. Eastwood had sent a script entitled The Hostiles to Wayne’s people in the hopes that two generations of western icon could appear on-screen together, but it was returned unread. When Eastwood sent the script again, this time Wayne replied with a personal letter telling Eastwood that HPD “wasn’t really about the people who pioneered the West” and it didn’t “accurately represent the spirit of the pioneers who had made America great.”

It was at this point that Eastwood knew he was barking up the wrong tree with Wayne because ‘The Duke’ had totally missed the point of HPD. “I realised that there’s two different generations, and he wouldn’t understand what I was doing,” the star admitted in an interview with Kenneth Turan. “High Plains Drifter was meant to be a fable; it wasn’t meant to show the hours of pioneering drudgery. It wasn’t supposed to be anything about settling the west.”

In the end, The Hostiles was never made, and the closest Wayne ever came to working with Eastwood was collaborating with Eastwood’s Dirty Harry director, Don Siegel, on his final film, The Shootist. Naturally, that didn’t go well, either, with Wayne reportedly disagreeing with nearly every decision Siegel made on-set. Siegel, for his part, told a local newspaper, “Wayne is supposed to eat directors for breakfast, but if he tries to eat me, he’ll get indigestion.”

Ultimately, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that Wayne’s anxiety surrounding Eastwood can likely be summed up nicely by a quote from Scott Eyman, the author of John Wayne: The Life and Legend. After all, he wrote that Wayne “was sensitive about the drift toward nihilism and probably felt a little threatened” – and that sounds about right.

Related Topics

Clint Eastwood